Faust’s Atonement: The Repudiation of Sexual Desire on Walpurgis Night

[This section follows from Part III, below]

Lilith, Adam’s first wife

John Collier, Lilith (1892)

IV. Faust's Atonement: The Repudiation of Sexual Desire on Walpurgis Night

To dampen Faust’s ardor for Gretchen, to remove him from the scene of his crime, and to cause him to sin against God, Mephistopheles has led Faust into his domain, the Brocken, on the night of the Witches’ Sabbath, into the ‘sphere of dreams and magic.’ His contempt for the crowds, however, initially diverts the travelers from their ultimate goal, but towards the conclusion of the Walpurgisnacht episode, the focus turns to Mephisto’s true design: to seduce Faust through sexual desire.

Faust himself has urged Mephistopheles onward to the summit, and chafes at the temporary diversion in the campsite of the émigrés (see Part III). He has made it clear he wants to see the place where the Devil Lord is encamped with the witches, and believes that this encounter will provide him with the key to human existence:

“Doch droben möcht’ ich lieber sein!

Schon seh’ ich Glut und Wirbelrauch.

Dort strömt die Menge zu dem Bösen;

Da muss sich manches Rätsel lösen.”

[But I prefer that higher region

Where even now I see a smoky, churning glow,

And crowds advancing to the Evil One;

Many riddles may be answered there.]

_by_Falero.jpg)

Walpurgis Night: a Neo-classical interpretationLuis Riccardo Faléro, “The Vision of Faust” (1878)

After listening to the laments of the émigrés, which had the effect of making Mephisto feel very old (see Part III), the two travelers come upon a ‘peddler witch’ (“Trüdelhexe”), whose wares are displayed about her and promoted in a manner chillingly reminiscent of the spectacle of the consumer society:

“Ihr Herren, geht nicht so vorbei!

Lasst die Gelegenheit nicht fahren!

Aufmerksam blickt nach meinen Waren,

Es steht dahier gar mancherlei.

Und doch ist nichts in meinem Laden,

Dem keiner auf der Erde gleicht,

Das nicht einmal zum tücht’gen Schaden

Der Menschen und der Welt gereicht.”

[Gentlemen, pray give me some attention!

Don’t pass up this opportunity!

Pay close attention to my wares

Some curious things are on display

You’ll find no single object in my shop –

The like of which you never saw on earth –

That has not caused at least on one occasion

Some splendid hurt to man and nature.]

Ernst Barlach, Illustration to Goethe’s Walpurgisnacht: Trüdelhexe

Faust believes he is seeing ‘the fair to end all fairs’ (“Heiss ich mir das doch eine Messe!”), but Mephisto is unimpressed, and dismisses the peddler with the blasé attitude of the seasoned consumer (Been there, done that!):

“Frau Muhme! Sie versteht mir schlecht die Zeiten.

Getan geschehn! Geschehn getan!

Verleg’ Sie sich auf Neuigkeiten!

Nur Neuigkeiten ziehn uns an.”

[Cousin, you are way behind the times.

What’s done is past! What’s past is done!

You should go in for novelties!

Something new is what we want.]

But material commodities fail to tempt Faust, and in an abrupt change of mood, he notices a woman, and points her out to Mephisto, whose opportunity to lead Faust to sin thereby finally arrives. For it is the Vision of Lilith:

“Faust: Wer ist denn das?

Mephitopheles: Betrachte sie genau!

Lilith ist das.

Faust: Wer?

Mephistopheles: Adams erste Frau.”

[Faust: Who is that?

Mephistopheles: Observe her very closely!

She is Lilith.

Faust: Who?

Mephistopheles: The first of Adam’s wives.]

In ancient rabbinic tradition, Lilith, Lamia in the Vulgate, was Adam’s first wife. She was banished from the Garden of Eden when she refused to make herself subservient to Adam by refusing to adopt the conventional ‘missionary’ position during sex. When she was cast out, she was made into a demon figure, and Adam was given a second wife, Eve, who was fashioned from his rib to ensure obedience to her man. In the Western tradition, Lilith has been depicted with Adam and Eve, as the serpent in the tree of knowledge.

Adam, Lilith, and Eve.

Left portal of the Western façade of Notre Dame, Paris. (ca. 1210)

Her name is first mentioned in Isaiah 34: 14, in the description of the desolation of Edom: “And wild animals shall meet with hyenas; the wild goat shall cry to his fellow; indeed, there the night bird (liylith) shall settle and find for herself a resting place.” There is a vast literature and considerable scholarly controversy regarding her identity, but tradition has her as an ancestral witch. She was said to have left Adam and mated with demons, begetting dangerous spirits, and in medieval and Renaissance books of magic she occurs as a frightening spirit, and is known as succuba.

Ernst Barlach, Illustration to Goethe’s Walpurgisnacht:

Lilith and the swine

Mephisto warns Faust about Lilith’s charms, while tempting him:

“Nimm dich in acht vor ihren schönen Haaren,

Vor diesem Schmuck, mit dem sie einzig prangt.

Wenn sie damit den jungen Mann erlangt,

So lässt sie ihn so bald nicht wieder fahren.”

[Be on guard against her lovely hair,

Against adornments that outshine all others

When a man is tangled in its toils,

Lilith will not lightly let him go.]

Faust notices that Lilith is accompanied by an older witch, and that both of them have been actively dancing about. Faust and Mephisto then take both women as dancing partners, Mephisto the old one (Die Alte) and Faust Lilith (Die Schöne), whilst engaging in reparte that is pure sexual innuendo:

“Faust (mit der Jungen tanzend):

Einst hatt’ ich einen schönen Traum:

Da sah ich einen Apfelbaum,

Zwei schöne Äpfel glänzten dran,

Sie reizten mich, ich stieg hinan.”

[Once I fell to pleasant dreaming:

I saw a sturdy apple tree

With two apples on it gleaming

I climbed it, for they tempted me.]

“Die Schöne: Der Äpfelchen begehrt ihr sehr,

Und schon vom Paradiese her.

Von Freuden fühl’ ich mich bewegt,

Dass auch mein Garten solche trägt.”

[Pretty witch: You want apples of a pleasing size;

You’ve looked for them since Paradise.

I am thrilled with joy and pleasure,

For my garden holds such treasure.]

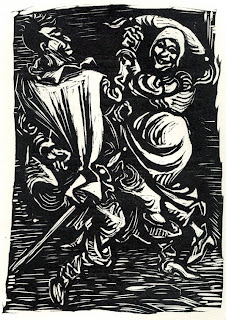

Ernst Barlach, Illustration to Goethe’s Walpurgisnacht:

Faust dances with Lilith

The ‘apples’ metaphor is a reference both to the Song of Solomon, 4:13, where Solomon expresses his love for his bride, (“Your shoots are an orchard of pomegranates, with choice fruits, henna with nard plants”), and to Satan’s seduction of Eve in Genesis. It is also a veiled reference to the young witch’s breasts. Mephisto’s reparte is, on the other hand, obscene, and Goethe deleted the more suggestive words in his first edition of the Faust, Part I:

“Mephistopheles (mit der Alten):

Einst hatt’ ich einen wüsten Traum;

Da sah ich einen gespaltnen Baum,

Der hatt’ ein ungeheures Loch;

So gross es war, gefiel mir’s doch.”

[Once I had a savage dream:

I saw an ancient, cloven tree

In which a giant hole did gleam,

Big as it was, it suited me.]

“Die Alte: Ich biete meinen besten Gruss

Dem Ritter mit dem Pferdefuss!

Halt’ Er einen rechten Pfropf bereit,

Wenn Er das grosse Loch nicht scheut.”

[Let me salute and welcome Him,

The Knight with the cloven hoof!

If He had not shied

away from the giant hole,

a giant stopper would ensure

That He could fill the aperture.]

[translation is my own]

Ernst Barlach, Illustration to Goethe’s Walpurgisnacht:

Mephistopheles dances with the Old Witch

After this witty dialogue between the partners, there follows the exchange with the Proktophantasmist, discussed in Part III, at which point Mephisto’s attention is distracted. The hiatus is fatal. When he turns again to Faust, the latter has ditched his dancing partner and stands alone. When Mephisto inquires for the reason, Faust tells him that he saw a scarlet mouse jump out of Lilith’s mouth as she was concluding a song (“Ach! Mitten im Gesange sprang / Ein rotes Mäuschen ihr aus dem Munde.”). Predictably, this baffles Mephisto:

“Das ist was Rechts! Das nimmt man nicht genau;

Genug, die Maus war doch nicht grau.

Wer fragt darnach in einer Schäferstunde?”

[That’s nothing much. You need not be alarmed,

The mouse was after all not gray.

Who’d ask questions in so sweet an hour?]

But the real reason for Faust’s disappointment with Lilith, and for the dampening of his ardor, is far more significant. It is, in fact, the denouement of the Walpurgisnacht episode in what turns out to be the defeat of Mephistopheles’ designs on Faust. Here Goethe shows to what extent he had been influenced by Kant’s works on the philosophy of Ethics during the course of the 1790’s, for what Faust does now is to elevate himself above the phenomenal world of intention and desire to the noumenal realm of Morality. His display of autonomous moral agency, which is in effect his bid for freedom from Mephistopheles’ wiles, is triggered by love. He has a vision of Gretchen, a reminiscence of the woman he has abandoned, and he will speak words of love. This alone accounts for his repudiation of carnal desire.

The broken-hearted Gretchen

Kathe Kollwitz, Gretchen (1899)

In the distance, Faust is struck by the vision of a girl who appears to be gliding slowly in fettered feet, and who resembles his ‘dear’ Gretchen (“dem guten Gretchen gleicht”). Mephisto attempts to distract him from his curiosity, and describes the vision as that of a mere magic shape, an idol. He reminds Faust of the Medusa, whose rigid stare congealed the blood of men (“Vom starren Blick erstarrt des Menschen Blut”), and turned them into stone.

Ernst Barlach, Illustration to Goethe’s Walpurgisnacht: The Vision of Gretchen

Faust is not deterred, however, and insists upon gazing on the vision of his beloved:

“Fürwahr, es sind die Augen einer Toten,

Die eine liebende Hand nicht schloss.

Das ist die Brust, die Gretchen mir geboten,

Das ist der süsse Leib, den ich genoss.”

[Now I see a dead girl’s eyes

Which were never closed by loving hands.

That is the breast which Gretchen yielded me,

The Blessed body I enjoyed.]

His recognition of her, which arouses both affection and guilt in his heart, is now compounded by a premonition of her death. He notes a crimson thread upon her throat, as if cut. The vision causes him both ecstasy and despair.

“Welch eine Wonne! Welch ein Leiden!

Ich kann von diesem Blick nicht scheiden.

Wie sonderbar muss diesen schönen Hals

Ein einzig rotes Schnürchen schmücken,

Nicht breiter als ein Messerrücken!”

[What ecstasy! What anguish and despair!

I cannot turn my eyes away.

How strange a single crimson thread,

No broader than a razor’s edge,

Would look upon her lovely throat.]

Mephistopheles knows he has been defeated, that Faust has turned his back on sexuality and carnal desire, and that the battle for his soul will still have to be waged again, on other fronts. The magic is broken. In the interim, though he has deliberately brought Faust to the Brocken because it is his own domain, a domain of ‘dreams and magic,’ he complains about how Faust is always hankering after phantoms! (“Nur immer diese Lust zum Wahn!”). He beckons Faust to the feast that is occurring on the summit, which he now describes as a ‘little hill’ (Hügelchen), because it is as lively as ‘the Prater,’ the notorious amusement park in Vienna, which had actually just opened as a public park very recently in Goethe’s own time, in 1766! In effect, though Mephistopheles does not say so, he has failed to capture Faust’s soul within his own realm and domain, the sphere of magic and illusion, and must now entice Faust with reality. The anachronistic reference to the Prater, the diminishment of the Brocken, the lame pursuit of the Perseus metaphor, are devises meant to bring Faust back to earth and make a direct bid for his carnal lust. But before Mephisto can conclude his bid, he can already tell that the episode is over and the curtain must fall on this act.

“Ganz recht! Ich seh’ es ebenfalls.

Sie kann das Haupt auch unterm Arme tragen;

Denn Perseus hat’s ihr abgeschlagen. –

Nur immer diese Lust zum Wahn!

Komm doch das Hügelchen heran,

Hier ist’s so lustig wie im Prater;

Und hat man mir’s nicht angetan

So seh’ ich wahrlich ein Theater.”

[Quite right. Now I can see it too. What’s more,

She also holds her head beneath her arm,

Since Perseus struck it from her trunk.

Must you always hanker after phantoms?

Climb up that little hill with me;

It is as lively as the Prater there.

And unless I’m totally bewitched,

I see a ready stage and curtain.]

Accordingly, the Walpurgisnacht episode concludes, appropriately, with a curtain fall. In comes “Servibilis” on stage, a huckster type such as one would find before a circus tent. His function is to end the Walpurgisnacht scene and, literally, set the stage for the following scene, the Intermezzo, entitled “Walpurgis Night Dream, or, Oberon and Titania’s Golden Wedding” (Walpurgisnachtstraum, oder Oberons und Titanias Goldne Hochzeit), which follows:

“Servibilis: Gleich fängt man wieder an.

Ein neues Stück, das letzte Stück von sieben;

So viel zu geben, ist allhier der Brauch.

Ein Dilettant hat es geschrieben,

Und Dilettanten spielen’s auch.

Verzeiht, ihr Herrn, wenn ich verschwinde;

Mich dilettiert’s, den Vorhang aufzuziehn.”

[We shall resume in just a moment

Another piece, the last of seven.

It is the custom here to show a lot.

An amateur composed the play,

And amateurs make up the cast.

Allow me, sirs, to disappear

And be an amateurish curtain-raiser.]

Mephisto, in a commentary on the play within the play, ironically responds:

“Wenn ich euch auf dem Blocksberg finde,

Das find’ ich gut’ denn da gehört ihr hin.”

[I am glad to find you on the Brocken,

For that’s the proper place for you.]

Two hundred years after the Walpurgisnacht scene was written, the Brocken has been secularized. Chorus of disembodied voices, spectacles of money and sexuality, are broadcast daily from the TV tower on top of the mountain. In the Museum, the intricacies of the mountain’s geology, the minute accounts of its literary reputation, the richness of its botanical varieties and the habits of its fauna, are methodically displayed. Today the mountain has been thoroughly explained; it can no longer be the “Traum- und Zaubersphäre,” the ‘sphere of dreams and magic.’ Would Faust turn his back on the Devil today?

No comments:

Post a Comment